In 2015, I took on the role of coordinator & compiler of the Hamilton Christmas Bird Count (HCBC) for the Hamilton Naturalists’ Club. Lately I’ve been poring through the vast amounts of data accumulated over the decades. In a series of short posts, I explore how the Christmas Bird Count records can reveal some interesting facts about bird species in Hamilton.

Carolina Wren: A Non-Migratory Resident

I believe it was in the mid-2000s when I first heard a Carolina Wren. I had no idea what I was hearing – it was a very loud bird that was surprisingly elusive, and the only bird calls I knew well enough to identify a species were rural farm birds and common urban birds. It wasn’t until the rise of mobile birding apps, which had actual recordings of bird species, that I finally identified the loud little wren.

But I hadn’t really heard of this wren before, so where did it come from?

Indeed the Carolina Wren has been pushing its territorial boundaries north for a few decades now. It is non-migratory – which means like some common birds we see year-round (Black-capped Chickadee, Northern Cardinal) – they generally do not migrate unless they need to find a new space. They breed and winter in the same territory.

All other wren species known to either breed or overwinter in Hamilton are migratory: the aptly named Winter Wren, also-aptly-named Marsh Wren, the summer-abundant House Wren, and rare and unpredicatable Sedge Wren. (The Sedge Wren is probably the best example of a migratory pattern taken to the extreme: individuals are known to breed in completely different parts of the continent year-to-year, having very low site fidelity.)

What is also of note is that while Carolina Wrens are tiny and like to hide from view, they are not shy when it comes to singing. Like some other resident species, they can be heard singing in the winter. Black-capped Chickadee males are known to also do this, to sing loudly during the coldest days as a way of attracting a mate or reaffirming to a mate that they are strongly suited to not only enduring the winter, but thriving and singing through it.

I’ve heard multiple Carolina Wrens singing loudly in -20°C weather in Hamilton. So there can be no doubt that when the HCBC data shows the rise in the count of Carolina Wrens, this is not due to the improved ability to find this species with the rise of digital cameras and birding apps, they do indeed call attention to themselves.

The Data

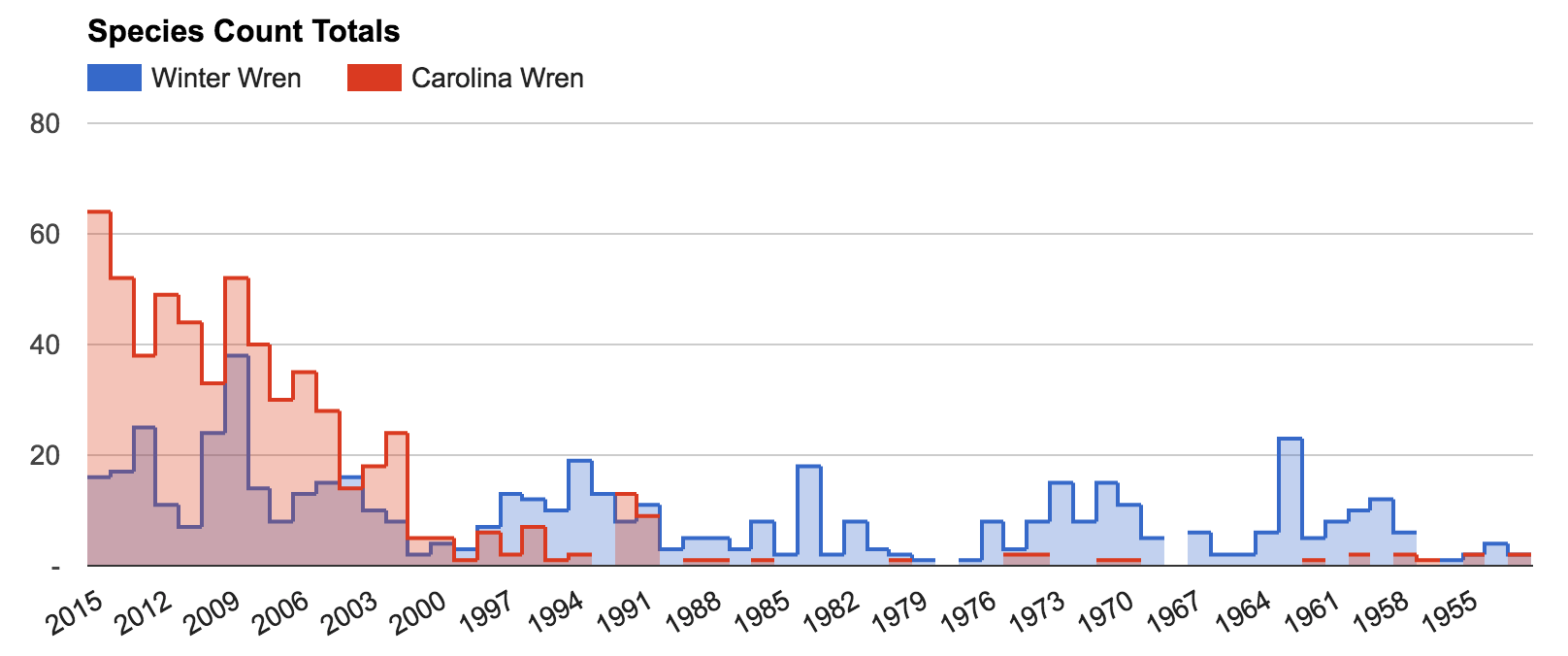

While the Winter Wren has been following a consistent ebb-and-flow pattern over the last 60 years, Carolina Wrens have been sporatically found in small numbers up until the late 1990s, and since then the count totals for this species have been taking off.

In fact, 2015 was the best year by far for this species, with a count of 64 individuals. The Carolina Wren quickly has surpassed the Winter Wren as the most common wren to find in Hamilton in the winter.

How many more Carolina Wrens could the region be host to? Many of the individuals counted are concentrated within the Cootes-to-Escarpment area, where there is better shelter and presumably more food for these tiny birds. They are also known to visit feeders as well, which also helps sustain the populations through harsh winters.

It was presumed by some that the very harsh 2014-15 winter would cause a significant die-off of the population of Carolina Wrens, but the record showing in late 2015 might very well be proof that our local stock is finally hardy enough to endure the harshest of winters.

A Carolina Wren singing. Loud for such a small bird. Dundas, Ontario #HamOnt #spring pic.twitter.com/06Y566UO4j

— Rob Porter (@rgeraldporter) March 30, 2015

For a while Hamilton was the most northerly range for this species, but it is still on the move northward. While non-migratory normally, as territories of pairs of birds are established some individuals are forced to move on to find territory elsewhere. One very ambitious individual was even found in Moosonee a couple years ago, though extreme migrants like that often do not establish breeding populations.

Is the Carolina Wren here to stay? Only time will tell, but with rising winter temperatures and plenty of bird feeders in Southern Ontario, it’s safe bet this loud little wren will be around for the foreseeable future.

Gallery: The Wren Family