In 2015, I took on the role of coordinator & compiler of the Hamilton Christmas Bird Count (HCBC) for the Hamilton Naturalists’ Club. Lately I’ve been poring through the vast amounts of data accumulated over the decades. In a series of short posts, I explore how the Christmas Bird Count records can reveal some interesting facts about bird species in Hamilton.

European Starlings

By now you likely know the stories about how European Starlings came to invade North America. What you may not know however, is how incredibly dominant this species was in the Hamilton Christmas Bird Count (HCBC) up until fairly recently, and how populations of starlings have begun to drop to much more reasonable sizes.

Some years it was almost the Christmas Starling Count…

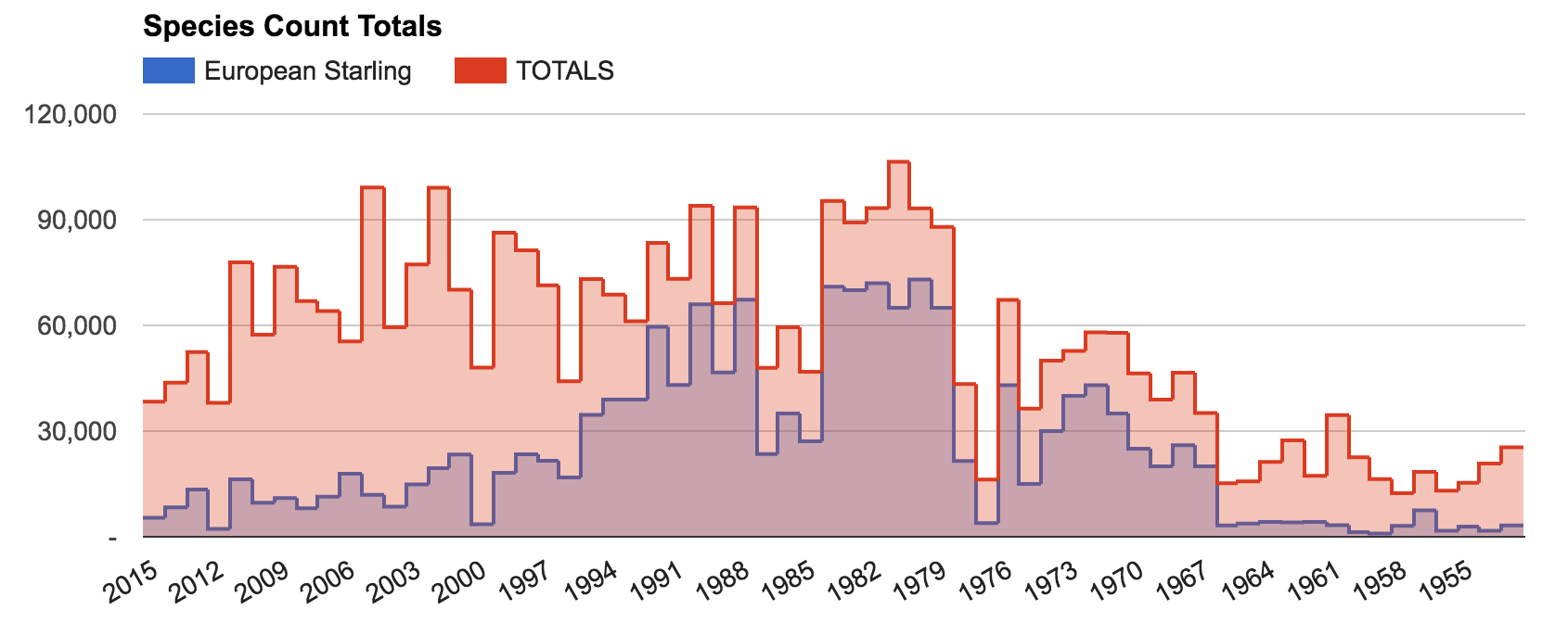

Yes, that chart is European Starlings vs all bird species counted during the HCBCs.

Here’s some observations about just how massive their numbers have been:

- From 1967 through the early 1990s, starlings accounted for over two-thirds of all birds counted

- At their peak year of 1980, starlings accounted for 73,000 out of the 93,000 birds counted – that leaves only 20,000 birds that were not starlings

- Since 1955, starlings accounted for almost a half of all birds ever counted: 1.5 million out of 3.4 million

- The very first count to include the European Starling was one lone bird in 1924; within four years there were over 1700 counted

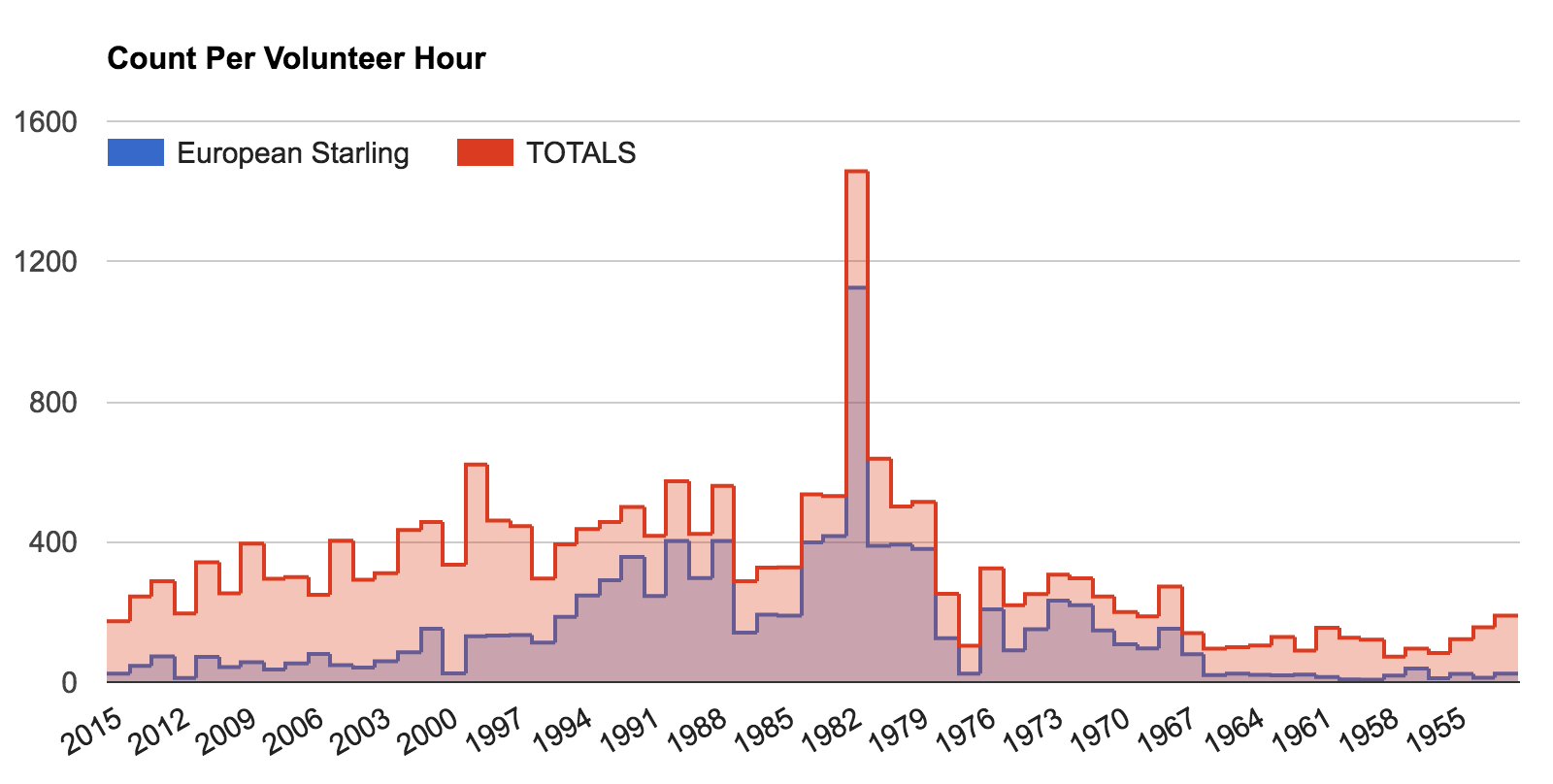

These ratios continue to hold true when accounting for volunteer count hours: there’s little chance of this being an observational error:

The starling populations have dropped though since the 1990s, settling down to being between 10-15% of the overall count. This is a much more reasonable population, considering starlings are species well known to accumulate in very large flocks, especially in winter.

A winter plumaged starling. Dundas, Ontario.#HamOnt #birds pic.twitter.com/wBFyGvyWzs

— Rob Porter (@rgeraldporter) January 27, 2015

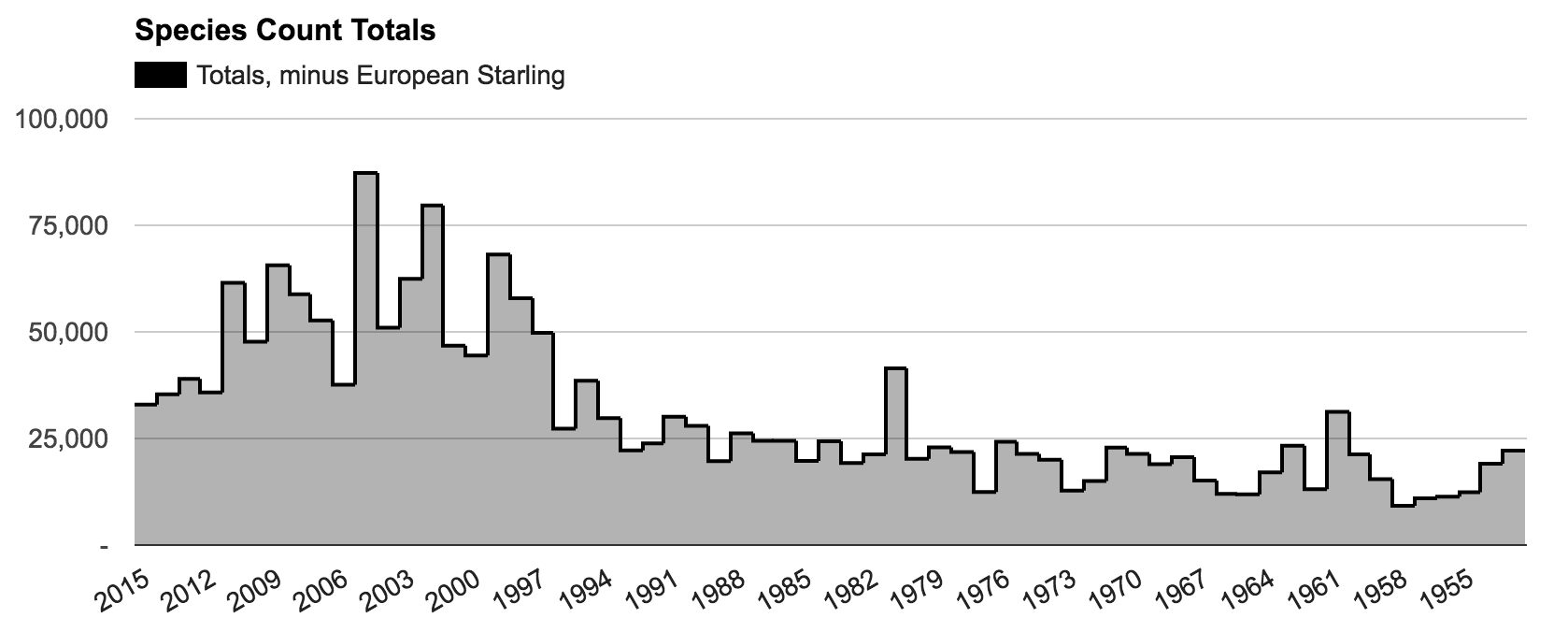

Since European Starlings have been so dominant in the count in some years, it is worth taking a look at what the count looks like without them at all.

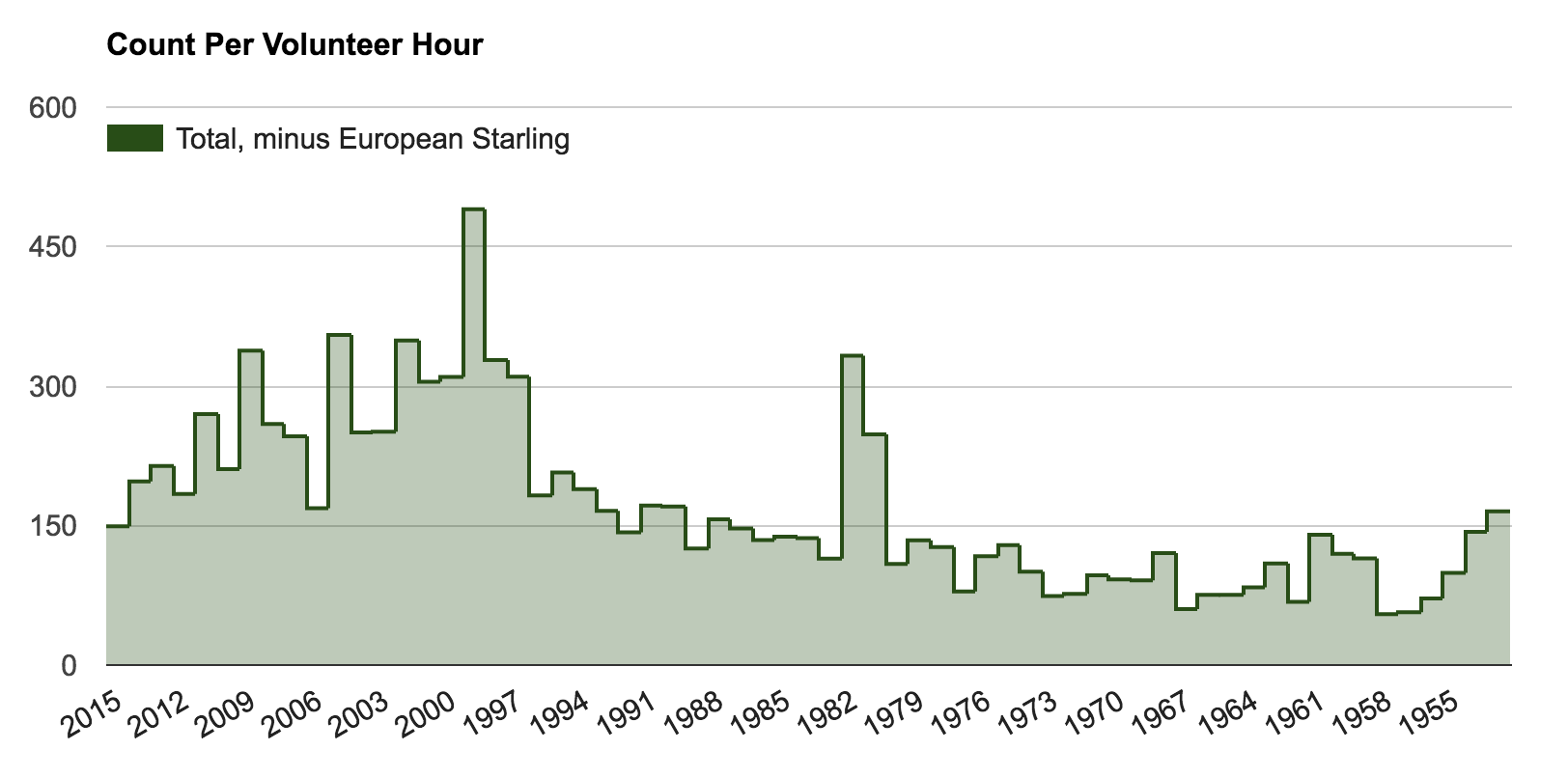

These charts show the total count without any starlings, followed by the per-hour rate of birds counted each year excluding starlings:

This reveals that non-starling populations actually significantly increased in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and are currently in a general decline.

Someday I’ll need to see if I can assemble a similar chart of non-indigenous species (NIS) vs indigenous species. Rock Piegons, House Finches, House Sparrows, and possibly Canada Geese (not NIS, but are re-introduced and arguably invasive) are just a few possible species that would be interesting to compare.

The invasions aren’t over yet, either. Very recently the first-ever record of a pair of Eurasian Collared-Dove breeding in Ontario was reported, and Eurasian Tree Sparrows have also been slowly headed towards this province. These species do not congregate in such dramatically large colonies as starlings, however, but still could serve as a competitive threat to Ontario’s native bird species.